Python: The Documentary

September 4, 2025

I just watched “Python: The Documentary” and absolutely loved it 🩵 Highly recommended!

Takeaway

The documentary narrates not only the technical milestones but the human journey:

- 🚀 How Guido van Rossum’s vision and persistence turned a small project (started over a Christmas break!) into a global phenomenon.

- 🚨How the community navigated tough transitions (obviously we are talking about Python 2 → 3) and came out stronger.

- 🐍 How tools like Anaconda helped Python explode in data science.

- 🩵 And how a culture of inclusivity transformed PyCon into a space that reflects the diversity of the wider world.

It’s fascinating to see that Python’s growth wasn’t just about clever design choices. Its real strength came from something deeper: A culture that welcomes ideas, contributions, and people. As Brett Cannon famously said:

Came for the language, stayed for the community. ✨

That sentiment really sums up what makes Python the world’s most loved programming language 🐍.

When GPUs Make Python Slower

August 22, 2025

Just finished watching this interesting talk from the PyconUS 2025 Conference.

Takeaways

Minimise memory transfers:

- The GPU is a separate device with its own memory (most modern GPUs rely on VRAM). To process data, you often need to transfer it from CPU (host) memory to GPU (device) memory and back again. These transfers happen over the PCIe bus, which is much slower than the GPU’s internal memory bandwidth.

- Pitfall: If you repeatedly move data back and forth in small chunks, the transfer latency dominates, and the GPU spends more time waiting than computing. This can make your code slower than a pure CPU implementation.

Maximise operational intensity:

- GPUs are designed for high throughput: they can perform billions of floating-point operations per second ( FLOPs). But if your kernel does only a few calculations per byte of memory accessed, then memory bandwidth — not compute power — becomes the bottleneck. This is called being memory-bound.

- Pitfall: Suppose you read 1 GB of data from memory and only do one addition per number. The GPU will be starved waiting for memory instead of flexing its compute units. A CPU, with better caching and lower memory latency, might actually run faster.

Do NOT launch lots of small kernels

- Launching a kernel has overhead (on the order of microseconds but an overhead at the end of the day). If you launch thousands of tiny compute kernels, the overhead dominates and your GPU sits idle most of the time. GPUs work best using large, parallel workloads.

- Pitfall: Using a GPU like a CPU — e.g., writing a loop on the CPU that launches a GPU kernel for every small task. This gives you none of the parallelism benefits and a major overhead.

🔑 GPUs shine when you can (1) keep data on the GPU, (2) give them lots of calculations/mathematical operations to chew on per byte of data, and (3) launch fewer, larger kernels rather than a ton of small ones. Misuse them, and they can be slower than CPUs due to transfer overheads, memory stalls, or launch bottlenecks.

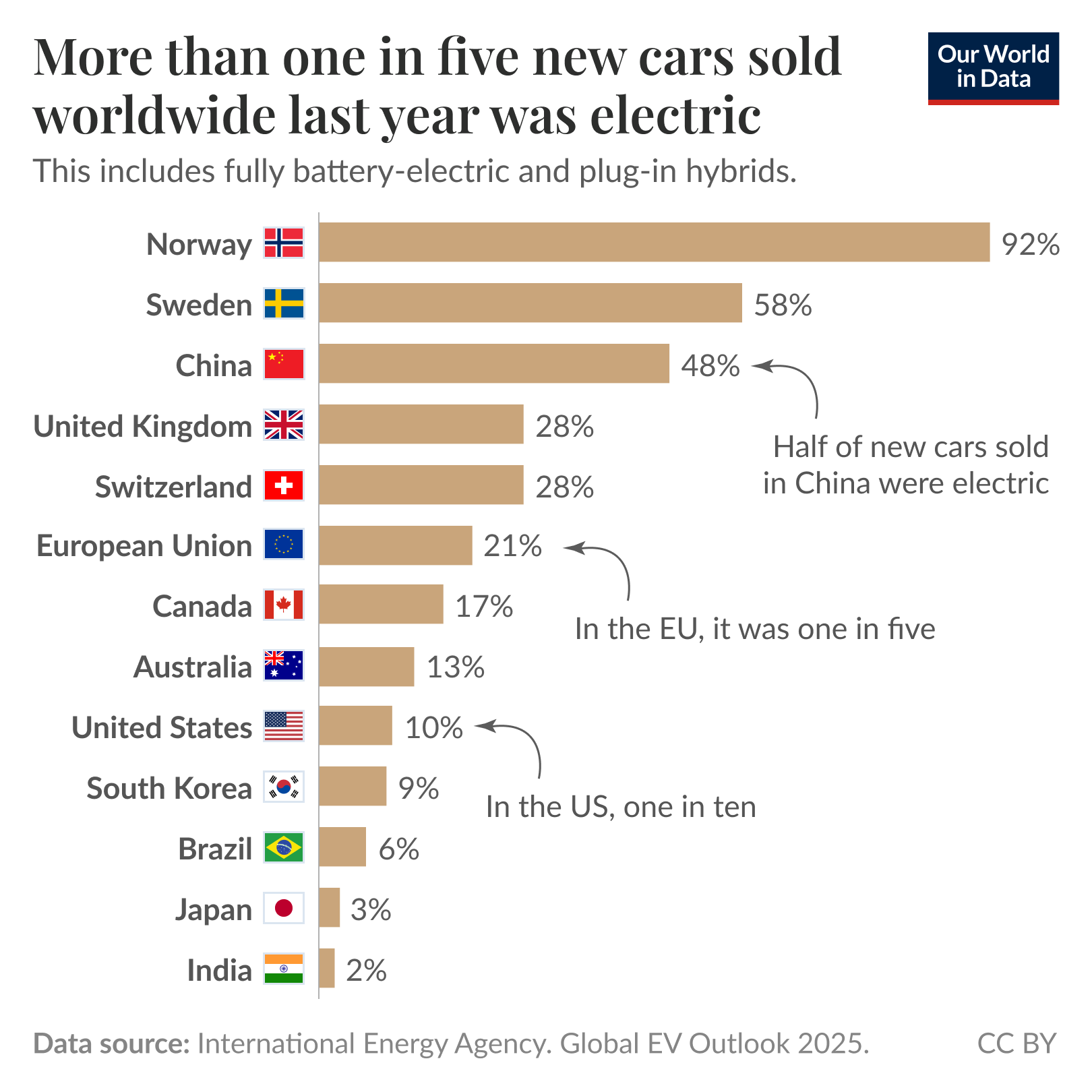

Chart of the Week

August 4, 2025

Source: Our World in Data

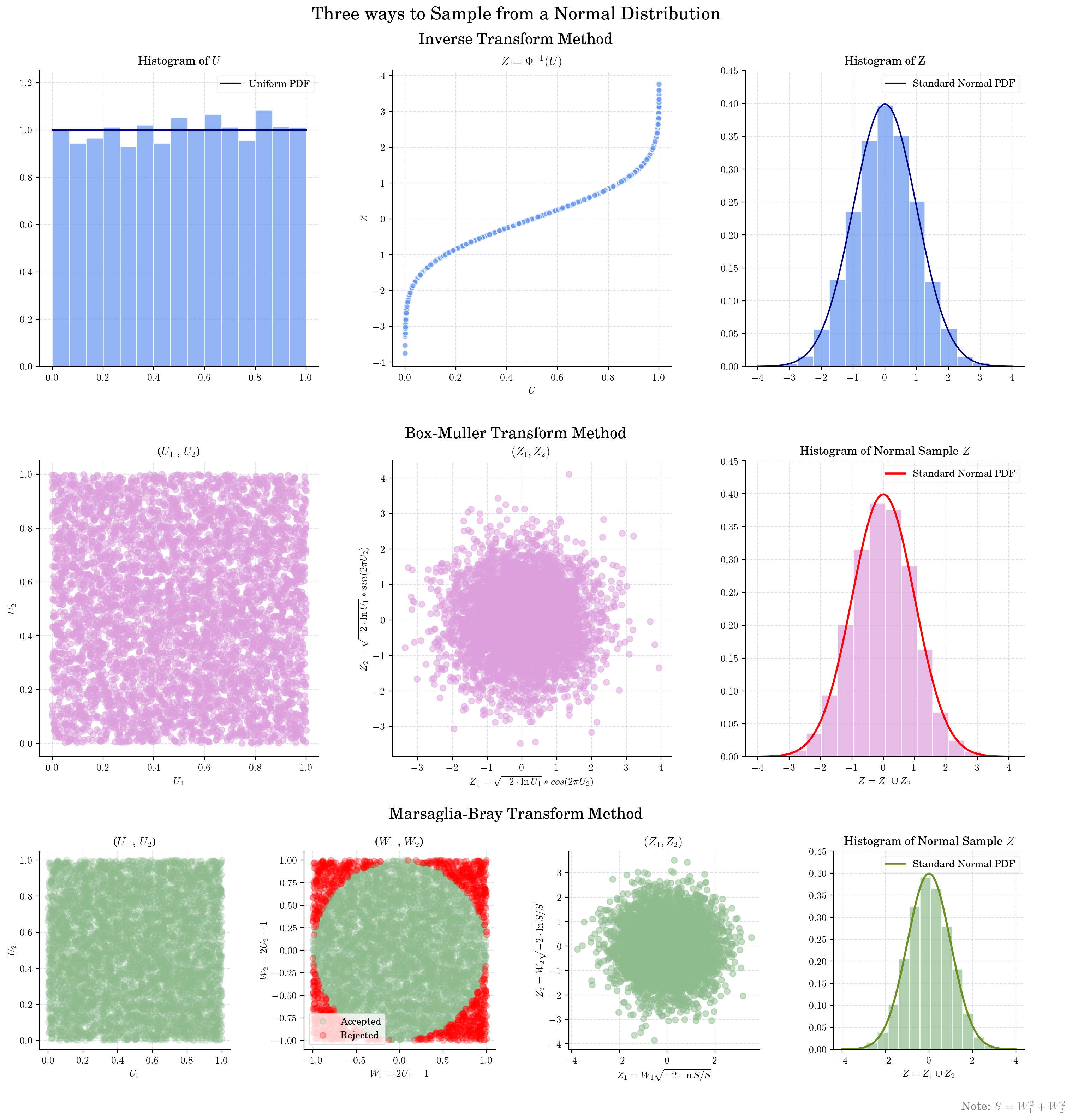

Normal Sampling

July 23, 2025

Made with 🩵 by Dialid Santiago.

Readings about A.I.

July 21, 2025

Just read this fascinating article in The New Yorker

Takeaways:

🔄 A.I. shifts our opportunity costs. “College is all about opportunity costs.” Students today spend far less time on schoolwork than in decades past. In the early 60s, college students spent an estimated 24 hours a week on schoolwork. Today, that figure is about 15 hours. With tools like ChatGPT, what used to take hours now takes minutes. But what are we giving up when we outsource the messy, formative process of thinking?

⚡ The intoxication of hyperefficiency. Most students start using A.I. as an organizer aid but quickly evolve to off-loading their thinking altogether. Moreover, they describe using it like social media: constantly open, constantly tempting. Are we becoming so efficient that we forget why we’re thinking in the first place?

✍️ Yes, typing is fast… “but neuroscientists have found that the “embodied experience” of writing by hand taps into parts of the brain that typing does not. Being able to write one way—even if it’s more efficient—doesn’t make the other way obsolete.”

🧍♂️ What does it mean to “sound like ourselves”? As AI gets better at sounding like us, do we risk forgetting what we sound like in the first place?

📉 Is Cognitive decline associated to A.I.? According to a recent study from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, human intellect has declined. The assessment of tens of thousands of adults across 31 countries showed an over-all decade-long drop in test scores for math and for reading comprehension. Andreas Schleicher, the director for education and skills at the O.E.C.D., hypothesized that the way we consume information today—often through short social-media posts—has something to do with the decline in literacy.

Books

July 18, 2025

The Diary of a CEO: Geoffrey Hinton

July 12, 2025

Just finished watching Geoffrey Hinton’s interview on The Diary of a CEO — a rare, candid conversation from one of the pioneers of AI.

Takeaways

-

Real AI risks are already here Hinton emphasizes that the pressing dangers aren’t sci-fi superintelligence, but things we see today: algorithmic manipulation, the amplification of bias, and disinformation at scale.

-

Hinton comes from a family tree of scientific legacy. His lineage includes George Boole best known as the author of The Laws of Thought (1854), which contains Boolean algebra; George Everest, a geographer and a Surveyor General of India, after whom Mount Everest was named; and Joan Hinton a nuclear physicist and one of the few women scientists who worked for the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos.

-

Hinton left his academic post not for ambition or prestige, but to earn enough to support his son, who has learning disabilities. His story highlights a quiet crisis: academia struggles to retain top talent when it can’t offer the financial security that industry can. What does it say about our priorities when some of the most important work in science can’t afford to support a family?

Related

- ← Newer

- 1 of 2

- Older →